Over the last few days, Japanese companies have been releasing their financial reports for the first quarter of their 2016 fiscal year. (That is, for the period from April to June 2016; the Japanese fiscal year doesn't follow the calendar year, but instead runs from April 1st to March 31st.) Among those doing so are both Olympus and Nikon, and neither report paints a pretty picture of the digital imaging market in the wake of the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake, which struck early in the fiscal year on April 16th, and whose damage was compounded by hundreds of aftershocks in the following days.

In its report, Olympus noted a whopping 25.5% decrease in its Imaging Business' net sales for the quarter, year-on-year. Mirrorless camera sales fell by some 23% to 10.8 billion yen in the same period, while compact camera sales -- a very small slice of the pie these days -- dropped by 25% to just 3.8 billion yen. Nor was the news from Nikon any better. Net sales for the company's Imaging Products Business in the quarter were down by 31%, and interchangeable-lens camera unit sales dropped by 32%. Nikon's compact camera sales in the quarter plunged even more precipitously, dropping some 45%.

But can much of this really be attributed to a natural disaster? Most people don't realize how devastating an impact the Kumamoto earthquakes have had on the camera industry. IR and other news outlets have told the story [Earlier articles here: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] of how the quakes shut down the major Sony camera-sensor plant there, and how that would impact most camera makers given Sony's dominant position in the sensor business.

Along with everyone else, we here at IR breathed a sigh of relief when Sony announced that the plant was operational again, as of May 13th 2016.

Phew! They got it back up and running, and chips are flowing off the production line again, right?

Well, not exactly. In fact, not at all.

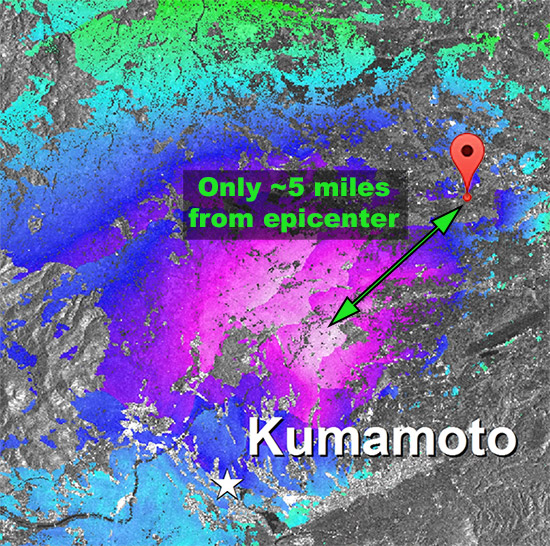

This was a major quake by any standard, measuring 7.0 on the Richter scale, but that's only part of the story. It was also a very shallow quake (6.8 miles or 11km below the surface), so ground shaking was much more severe than it would have been in a similar-magnitude event happening many miles underground. It was an 8.8 on the Mercalli scale, based on the effects of quakes vs their moment magnitude. That level would normally correspond to a Richter-scale quake of 8.0 or higher.

And the Sony Kumamoto Technology Center was only about five miles from the epicenter.

So this was a very severe quake, and the Sony sensor plant was sitting nearly on top of it, just a few miles away. The entire area was devastated, with landslides cutting both road and rail routes into the area. (We were told by an industry source outside Sony that it took them a week just to get into the plant.)

Sensor manufacturing involves literally hundreds of steps, with many of them requiring critical process control, extraordinarily precise alignment, and the complete absence of dust particles. If anything goes wrong in any of these areas, an entire batch of chips can be lost.

Now imagine a major-magnitude earthquake, power failure, the likely breaching of cleanroom areas, and ultra-precise wafer-patterning equipment being shaken a few feet in each direction. (That's probably an understatement; the ground along the fault line ended up being shifted by 1.8 meters laterally, and raised up 70 centimeters. Furthermore, it appears that the 1.8 meter movement happened in just 20 seconds.)

It only takes a moment's thought to realize that this wasn't a matter of a factory having to shut down until they could get the lights back on and mop the floors. To the contrary, all work in process was lost. This means that, once they got the plant running again, the entire manufacturing process had to start from scratch, starting from raw wafers.

The complexity of the semiconductor fabrication process means it takes a long time from raw wafer to finished sensor. A loooong time. About three months. So after the production resumed on May 21st, it would require three months, give or take, for the first sensors to start coming out the other end. In other words, the first chips since the quake will only be starting to ship sometime about now.

The industry didn't lose just 36 days or so, it lost more than four months of production. A third or so of an entire year's output. But wait, there's (probably) more...

Sony has made no comment on the internal state of the plant, but it's hard to imagine that a lot of delicate equipment wasn't badly damaged, at least some of it to the point of needing to be replaced or significantly overhauled. But these aren't machines you can just run down to the corner superstore to pick up another one. Many will be build-to-order items, with long lead times.

So as an industry, we're not out of the woods yet. Even if sensors are about to start coming off the line again, they probably won't be doing so as quickly as before the quake.

The good news, though, is that thanks to herculean efforts on the part of Sony's manufacturing engineers and plant employees, chips are about to start flowing out to the market again, and we are going to see new products being announced again in the runup to this year's Photokina show in late September. All indications are that this fall is going to be an exciting time in the camera business!

Source: Olympus, Nikon reveal big sales drops: Why the Kumamoto quake devastated the camera industry

No comments:

Post a Comment